Ancient Egypt has always lived at the intersection of fact and imagination. For us Egyptians, it’s not just history it’s part of who we are. Yet when we look at how the world has portrayed our civilization, it’s hard not to feel a mix of pride and frustration then when you think about it, it’s mainly frustration. Global cinema has been drawn to Egypt’s temples, pyramids, and pharaohs like moths to flame, but too often those stories have been told without Egyptians, without understanding, without the life that made this civilization real.

Across Hollywood and other global productions, ancient Egypt became less a society and more an aesthetic a convenient shorthand for drama, mystery, and exotic danger. The early biblical epics set the stage: huge sets, grand music, and Egypt as a backdrop for someone else’s story. When “Egypt” appeared on screen, it was pyramids in blazing sun, priests chanting in massive halls, queens dripping in impossible gold. But rarely did it show the people behind those monuments the farmers, artisans, scribes, or the women who had property and authority. Cinema made Egypt monumental but empty. The imagery was dazzling, but the context, the humanity, was missing.

In the 20th century, things didn’t get much better. Cleopatra became a Western obsession, constantly reinterpreted through foreign anxieties and aesthetics. Gods became CGI monsters, mummies turned into horror clichés. Casting choices erased the complexity of our own people, turning the pharaohs into a vague, exotic “other.” Even when filmmakers meant to be respectful, they rarely got the story right. For a hundred years, the world saw Egypt on screen but Egyptians themselves were mostly absent.

Meanwhile, Egyptian cinema, the industry with the strongest claim to these stories, spent decades circling around pharaonic history without ever fully landing on it. From the silent era to the golden age, our filmmakers were drawn to social dramas, political tensions, and urban realities stories that felt immediate and relatable then the empty silly attempts of comedy nowadays which reminds us of the Video Movies Era, and the pharaohs seemed distant, expensive, technically challenging, and perhaps politically loaded for a country still defining its modern identity. When the state later used cinema as a tool of nationalism, the focus shifted further to contemporary struggles; ancient history became a motif, not a subject. Even as technology improved and audiences became more adventurous, Egyptian cinema stayed away from our rich ancient Egyptian heritage. The pharaonic world appeared on TV, in documentaries, in stage productions but rarely on the big screen as a lived reality.

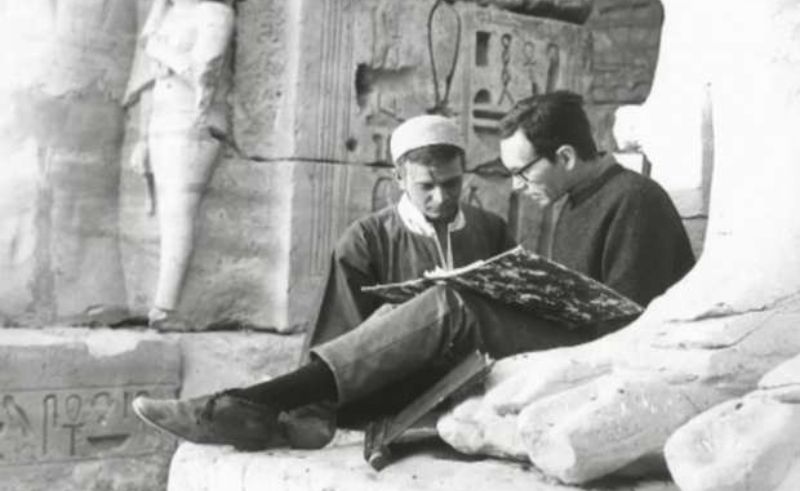

Then came Shadi Abdel Salam. Al-Mummia (The Night of Counting the Years, 1969) remains the benchmark for what an authentically Egyptian historical film can be. He didn’t chase spectacle or glamour. He treated history as responsibility a question of identity passed down through generations. His Egypt was simple, silent, moral, human. The power of the film isn’t in its sets or costumes, but in the way it asks us to reflect on our connection to the past. Even now, decades later, it’s the standard that Egyptian cinema has yet to fully follow.

Another landmark in Egyptian cinema that approached our past with authenticity is Youssef Chahine’s El Mohager (1994). While not strictly a historical epic, the film demonstrates how Egyptian filmmakers can blend personal stories with historical context, evoking the spirit, struggles, and identity of Egyptians across time. Chahine’s attention to character depth, moral complexity, and cultural nuance makes El Mohager a compelling example of storytelling that respects our heritage, proving that it is possible to create films about Ancient Egypt that feel lived, human, and inherently Egyptian.

The truth is uncomfortable: when Egypt left its own stories untold, others rushed in. Global studios told them, often prioritizing exotic over truth. The ecological balance, real life drama, stories of major historic events, laws and rituals that defined real ancient life were replaced with curses, sandstorms, and supernatural battles. Even the grand human dramas of Egyptian history political revolutions, monumental building projects were ignored.

Today, things feel different. With the Grand Egyptian Museum finally open and audiences craving stories with depth and authenticity, the world doesn’t want Egypt as fantasy they want Egypt as civilization. They want to see Hatshepsut navigate power in a male-dominated court, the artisans at work, scribes managing grain, Akhenaten’s spiritual revolution as politics, not myth. They want Egyptians telling these stories, with all the nuance and emotion that comes from living in this culture.

This is a challenge and an opportunity for our film industry. Egypt has the richest historical archives in the world, filled with letters, architectural plans, and papyri, waiting to be translated into cinema. We could lead a new wave of historically grounded films, not by copying Hollywood, but by showing something no one else can: the stories lived by our ancestors, told by us. With modern technology, international co-financing, and streaming platforms hungry for fresh, authentic history, the time is right.

What’s needed is courage. Courage to build worlds as ambitious as the pyramids, to trust our actors, designers, writers, and historians with these stories. To replace glossy, foreign fantasies with the intimacy of Egyptian memory and perspective. Egypt is not just a set for spectacle it is one of humanity’s first storytellers. And cinema, our youngest art form, is waiting for Egypt to speak in its own voice.

If the world has spent a century imagining Egypt, then Egyptian cinema’s next century must be about remembering it. Not as myth, not as ornament, but as people. Because the real epic of ancient Egypt wasn’t its monuments it was the minds and hands that built them. And finally, the world is ready to see them.