There are rare breeds of cinema that don’t merely tell a story — they inhabit your very senses. Ryan Coogler’s Sinners is precisely that kind of film: a potent, almost visceral experience that doesn’t just unfold before you but pulses, aches, and whispers its secrets deep within the fabric of every frame. It doesn’t simply request your attention — it demands your complete surrender. From the first moment its raw, unmistakably blues-infused soundscape washes over you, you’re not just watching a movie; you’re being drawn into an immersive world where the boundaries between narrative, sound, and emotion blur.

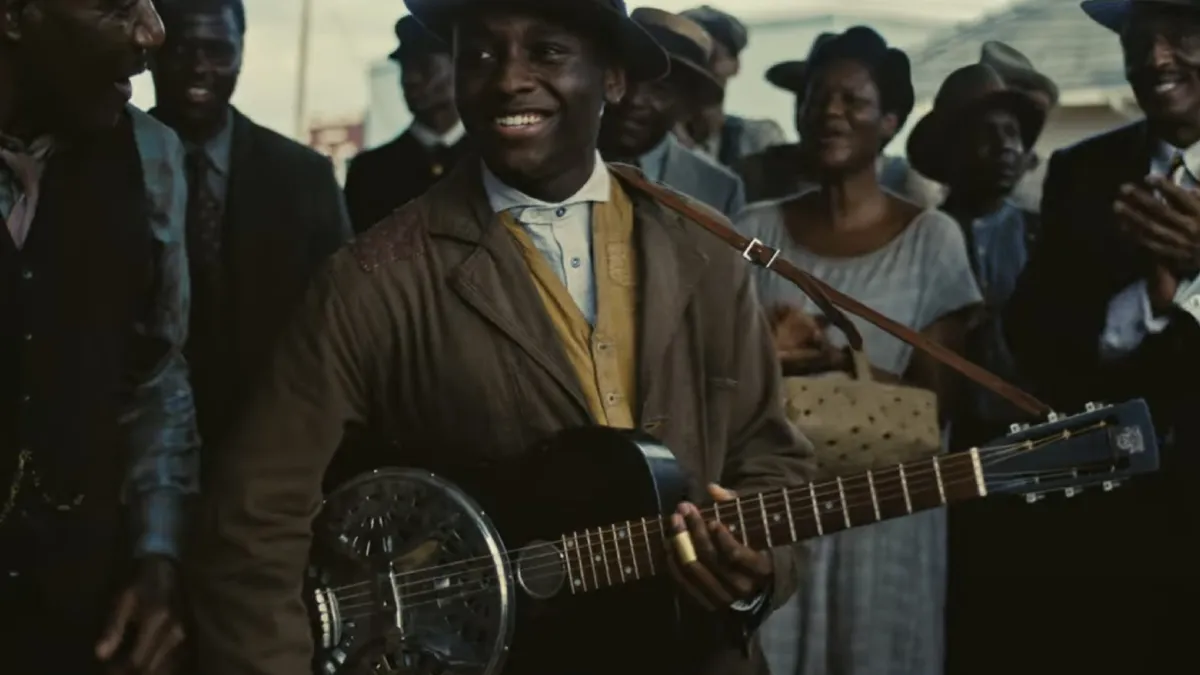

Here, the blues isn’t just a stylistic flourish or nostalgic backdrop; it is the very soul of the narrative — a living, breathing entity that acts simultaneously as narrator, conscience, and silent witness. It seeps into every corner of the humid Mississippi air of 1932, its melancholic currents infusing the lives of the characters as much as the landscape itself. Nowhere is this symbiosis more palpable than in the film’s deeply resonant juke joint scene, featuring Samuel, portrayed with a haunting, magnetic brilliance by newcomer Miles Caton. This pivotal sequence — best left unspoiled — transcends mere performance. It captures the distilled essence of Sinners: a space where music, history, tension, and fate intertwine so tightly that the inevitable feels both devastating and sublime.

This scene doesn’t just advance the plot; it sets the soul of the film ablaze.

In Sinners, the casting is impeccable, with every role — from the leads to the smallest extras — fitting seamlessly into the film’s world. Michael B. Jordan’s performance is nothing short of career-defining. He doesn’t just play two characters; beyond physical traits he inhabits two souls, obliterating the stigma of dual roles with precision and depth setting a quietly revolutionary benchmark for actors navigating dual roles in modern cinema. . Miles Caton’s debut as Samuel is raw and unforgettable, while Wunmi Mosaku delivers a nuanced, graceful power. Omar Miller’s balanced performance is a masterclass in restraint. But the real showstopper is Delroy Lindo’s portrayal of Delta Slim. It’s not just acting; it’s an immersion into a character that feels like it has always existed. This is an Oscar-worthy performance that sets a new bar in cinema.

Coogler’s directorial mastery courses through every frame. His camera glides with the languid grace of a blues riff — smooth, unhurried, yet capable of surprising emotional jabs that catch you off guard. The editing sings in perfect harmony with the sound design; each cut, each transition rises and falls with a rhythmic musicality that feels less like conventional filmmaking and more like an intricate, live performance, unfolding before your eyes and ears simultaneously. This profound synchronicity isn’t limited to just the camera and sound — it extends to every department. The evocative production design, the carefully sculpted chiaroscuro lighting, and the meticulously chosen costumes are all finely attuned to the film’s melancholic key, reinforcing the story’s historical weight while crafting an atmosphere that feels as textured and layered as the blues itself.

But what truly sets Sinners apart is its audacious and seamless blending of genres. Coogler orchestrates a delicate, masterful dance between creeping dread and unexpected bursts of laughter. A sharply executed jump scare — always earned, never cheap — can effortlessly dissolve into a moment of genuine, human comedic timing. These tonal shifts are not distractions or conventional relief valves; they are intrinsic to the film’s unpredictable rhythm, mirroring the emotional complexity of the blues, where sorrow, resilience, irony, and catharsis often coexist in the same breath. This tonal fluidity keeps the audience perpetually engaged, never allowing complacency.

Beneath these surface thrills runs a thematic river of remarkable depth. Sinners offers a piercing exploration of oppression’s insidious cycle, laying bare how violence emerges both as a consequence of injustice and as a tool for further manipulation and control. The introduction of vampires — far from a mere genre gimmick — serves as a potent, visceral metaphor. These creatures embody exploitation itself: they are living symbols of systemic racism’s predatory nature, draining life, autonomy, and humanity from the oppressed. Coogler handles these thematic layers with remarkable subtlety and restraint. He resists the temptation to overstate or over-explain, allowing the symbolism to resonate organically. Whether viewers choose to engage deeply with these allegorical undercurrents or simply follow the gripping surface narrative, the film offers rich rewards on both levels.

Visually, Sinners is a lush and deliberate creation. The carefully curated color palette, meticulous grading, and the dramatic interplay of light and shadow craft a world that feels both firmly grounded in historical reality and subtly unmoored, slipping just enough into dreamlike surrealism to reflect the film’s bolder narrative ambitions.

By the time the raw energy of metal guitar briefly echoes the foundational blues, bringing the musical journey full circle, the thematic resonance is undeniable and electrifying. The blues — the wellspring of so much modern music — returns here not just as a historical artifact, but as a hauntingly relevant prophecy, reminding us of the cycles that persist and the stories that refuse to be silenced.

Walking out of Sinners, the lingering sensation is profound and difficult to shake. Time seems to have dissolved within its immersive embrace, leaving you with echoes of its music, images, and ideas long after the credits have faded. This isn’t just a well-crafted film; it’s a rare cinematic experience that transcends its medium, lingers in the bloodstream, and — like the blues itself — speaks to something elemental and eternal.

Rating: ★★★★★★★★★☆ 9/10

Agreed, great effort keep it up

Thank you, appreciate the time you spent reading