The premise of Sentimental Value is, on the surface, simple and quietly familiar. A father returns. Two daughters stand before him. A house full of memories waits to be reopened. Gustav, a once celebrated film director who has long been absent from his children’s lives, comes back after the death of their mother, carrying with him not only unresolved guilt and emotional distance, but also a new project. He wants to make a film, one rooted in the family’s past and in the very home that still holds their shared history. Nora, his eldest daughter, now a respected stage actress, is his first choice for the lead. She refuses. The role then goes to Rachel, a famous foreign actress who enters this fragile family space as both a professional collaborator and an emotional intruder. Agnes, the younger sister, watches all of this unfold with a quieter, steadier presence, carrying her own version of the same childhood, the same absence, the same memories, yet shaped by them in a completely different way.

From this setup, the film does not rush toward confrontation, It breathes, it settles into the rooms, the hallways, the silences between words. The story unfolds the way memory does, not in clean cause and effect, but in emotional echoes one moment opens into another. A look carries more weight than a line of dialogue, a pause can say what years of distance could not. This is not a film built on events stacking on top of each other. It is built on living inside sequences, on feeling time pass, on sensing how a family’s past still hums under every present interaction.

What immediately stands out is the camera, its movement is gentle, almost tender it sways rather than shakes, in many films, a floating or handheld camera brings anxiety, instability, a sense of being off balance. Here it feels like something else entirely it is closer to being rocked in a chair, a soft, steady motion that carries you through the space instead of throwing you around inside it. The camera does not announce itself, it listens and glides through rooms, lingers on faces, drifts between characters as if it is trying to understand them rather than interrogate them. That softness does not weaken the emotion. It deepens it. It allows the tension to exist without forcing it.

The choice of shots follows the same philosophy. Frames are composed with care, but never with vanity every angle feels motivated by where the characters are emotionally, not by a desire to impress. When two people sit across from each other, the space between them is felt and when someone stands alone in a room, the room answers bac, the house itself becomes a presence doors, windows, staircases, corners filled with light or shadow all carry the weight of what once happened there and what still refuses to leave.

Editing plays an equally important role in shaping this experience. The cuts flow with a quiet confidence, even the transitions to black, which could have felt abrupt or mannered, are placed with such precision that they register like gentle blinks, moments where the film closes its eyes before opening them again. There is a tactile quality to this rhythm it feels crafted by someone who understands that timing in cinema is physical, almost like handling a delicate object, one wrong movement and the spell breaks. Here, every cut feels like placing a diamond on a ring, exact, patient, and aware of the value of what is being held.

Color, too, works in a subtle but powerful way. The palette seems to be anchored by the tones introduced early in the film, particularly the colors of the awnings outside the family home, those hues quietly echo throughout the movie, spreading into interiors, clothing, light, and shadow. It creates a visual continuity that is felt more than consciously noticed, as if the film has chosen its emotional key in the opening notes and continues to return to it, again and again, in different variations.

Before discussing the acting as a collective force, there is a performance that quietly anchors the entire emotional architecture of the film: Stellan Skarsgård as Gustav. What he does here is not built on showy moments or dramatic outbursts, but on a constant inner tension that never fully settles. His Gustav carries authority the way an old habit carries weight, but underneath it there is hesitation, regret, and a longing that does not quite know how to speak for itself. Skarsgård allows these layers to coexist in the same frame, a single look can suggest pride, defensiveness, and a fragile hope for forgiveness all at once. He plays a man whose identity has been shaped by creation, by control, by the need to shape stories, and who now finds himself facing the parts of life that cannot be directed or edited. The performance feels lived-in, weathered, and quietly painful, capturing the way time and choices leave their marks not in grand gestures, but in posture, in voice, in the way silence is held.

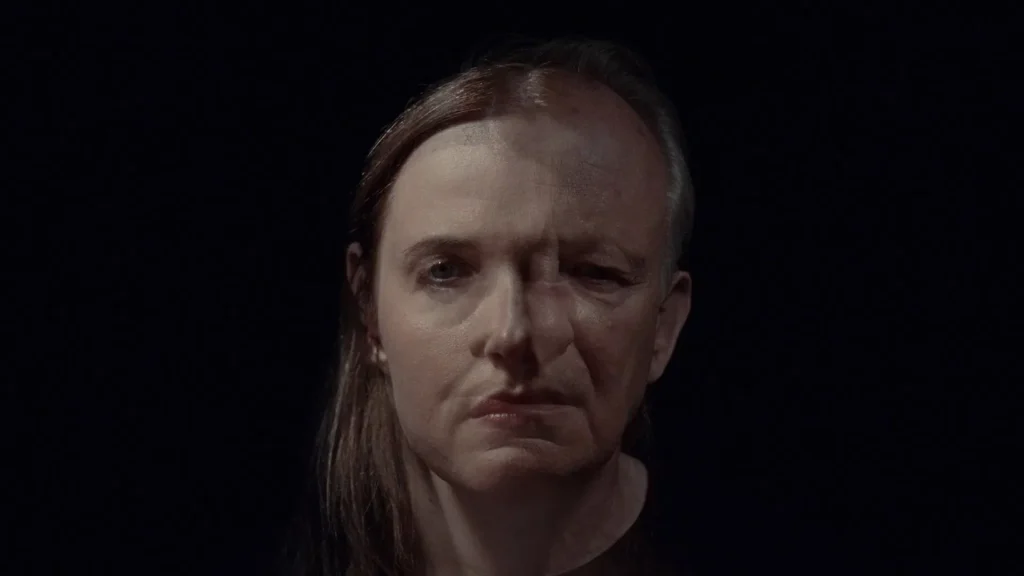

The acting across the film shares that same sense of emotional precision and restraint. Renate Reinsve gives Nora a nervous intensity that feels rooted in thought rather than display, as if every feeling has already passed through layers of self-analysis before reaching the surface. Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, as Agnes, works in a different register, calmer and more grounded, yet her stillness carries its own history and its own quiet ache. Elle Fanning’s Rachel enters the story with an apparent confidence, but gradually reveals uncertainty and sensitivity beneath it, making her presence feel human rather than symbolic. What connects all these performances is their trust in understatement, no one pushes for effect, emotions arrive through glances, timing, and the spaces between lines. The result is an ensemble that feels less like actors performing roles and more like people sharing a past, a present, and a complicated emotional terrain they are all still trying to navigate.

Then there is the title. Sentimental Value. At first, it might sound almost ironic, or even faintly dismissive, as if emotion itself is being priced and measured, but the more the film unfolds, the more the title reveals its depth. This is a story about what things are worth, not in money, but in memory a house, a role in a film, a childhood moment, a sentence spoken too late each carries a value that cannot be calculated, only felt. And that value differs from person to person, the same event can live in two siblings in completely different ways.

That idea runs through the heart of the story. The film is deeply concerned with perception, with how memory is shaped by personality. Nora and Agnes grew up in the same home, with the same father, the same mother, the same absences, yet what those experiences became inside them is not the same. Nora carries her past like a wound that never fully closed, one that has fueled her art but also left her exposed. Agnes has built a life that looks steadier, more grounded, yet she is no less marked by what happened. Their father, Gustav, carries his own version of the story, one filtered through ego, regret, and the self-justifications of a man who chose his work over his family and is only now trying to understand the cost.

What makes the film quietly disarming is its sense of human humor. It is not a comedy, yet it is often gently funny and emotional in the same time. Not in the way of punchlines or jokes, but in small, human observations. A line delivered with unexpected dryness, an awkward pause that becomes almost tender, a situation that is absurd in its honesty. This soft, sneaky humor does something important. It brings the characters closer to us. It reminds us that even in the middle of emotional reckoning, people remain people, they stumble, they say the wrong thing, they smile when they are nervous and they find themselves amused by the very situations that are breaking their hearts.

In the end, Sentimental Value is deeply moving, not because it reaches for grand gestures, but because it understands the quiet weight of things. The way a memory can sit in a room long after the people who made it are gone. The way love and disappointment can coexist in the same breath. The way art can both heal and reopen wounds. It is a film that does not push its emotions onto the audience. It invites them in, gently, and lets them settle. Like sitting in that rocking chair, feeling the slow, steady motion, and realizing that in the calm, something inside you is still being stirred.